Parents and Providers’ Voices are Essential to Building a Universal, Accessible ECE System

Insights

May 23, 2023

By: Marija Drobnjak and Cristina Onea

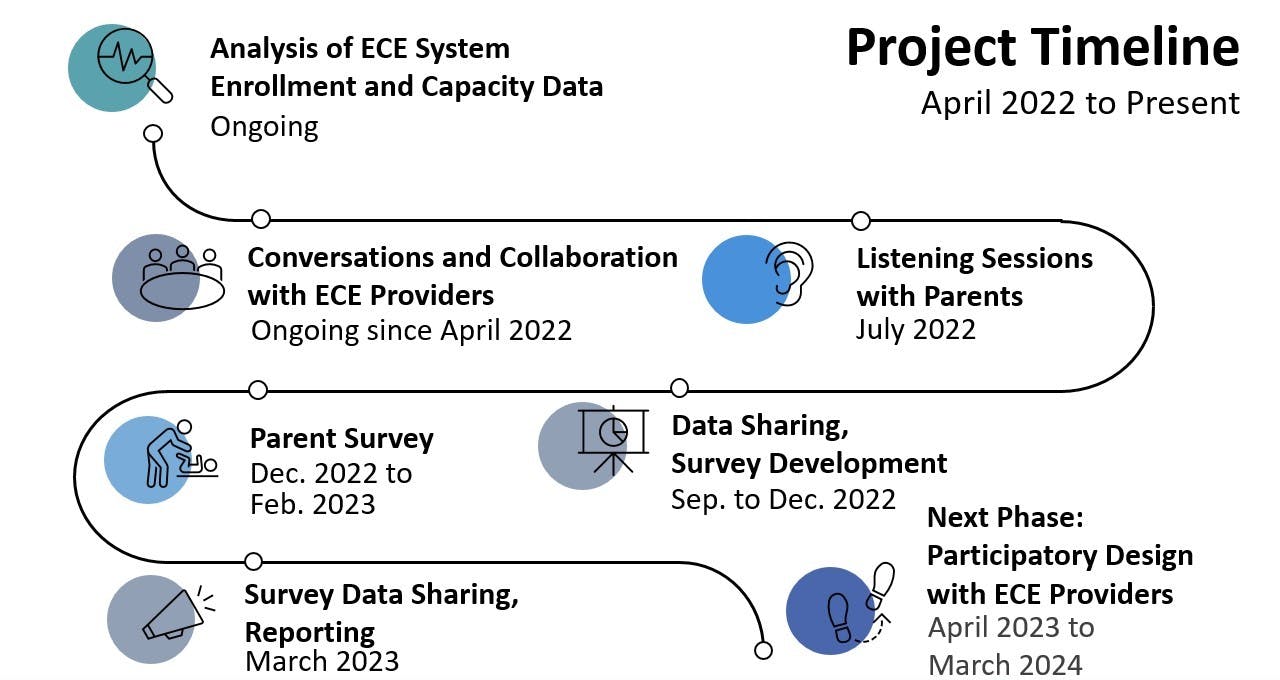

Earlier this month, CCC released, The Youngest New Yorkers: Building a Path Toward a Universal Early Care & Education System in New York City, a report summarizing our year-long, community-based research on barriers families face in accessing New York City’s early care and education (ECE) programs, which relied on analyzing administrative data on enrollment and capacity in ECE programs, collaborating with ECE providers to hear their perspectives, and speaking with parents with young children.

CCC has long relied on NYC parents and service providers’ to shape our understanding of child and family well-being, as well as our advocacy for policies that better meet communities’ needs across a host of issues through our community-based assessments and as a co-convener of the Campaign for Children.

Why We Use Participatory Research

By collaborating with NYC parents and providers, who have a stake in a robust ECE system, we aimed to ensure that the knowledge we have built as an organization is equally informed by community members. Participatory approaches to research prioritize the voices of people with lived experience, placing them at the forefront of defining the barriers they face and the solutions that would most effectively address them.

- When people are involved in decision-making, they are more likely to collaborate because they are invested in program outcomes.

- When a variety of families and providers participate there is a greater likelihood of representing the diverse communities served.

- When more perspectives and needs of all families are represented, there is more potential for equitable outcomes for all children.

This approach aligns with CCC’s vision, mission, and values, including and especially centering the perspectives of NYC children, youth, families, and community members from diverse backgrounds to ensure that knowledge is co-constructed with those who know, firsthand, how to create a more equitable experience for all.

How We Collaborated with ECE Providers

Providers’ contributions were critical for all stages of the project. Their day-to-day experience working with families and supporting them while managing multiple operational challenges as a city contracted providers contextualized the administrative data, qualitative findings, and informed our collaboration with families. Additionally, project partners and providers were instrumental in informing the design of the parents listening sessions and parent survey and in broadening outreach to families with young children, both to those enrolled in ECE programs and those who are not.

Throughout the project, between spring of 2022 and spring 2023, we:

- Reached out to and connected with close to 100 staff across 30 child and family service organizations, including contracted ECE program providers, as well as organizations providing an array of services for families and children.

- Conducted over 10 data sharing sessions, on average attended by 10 to 20 participants, to share findings and gather feedback and additional insights related to administrative data analysis, listening sessions with parents and citywide survey.

- Organized over 30 meetings with multiple staff from over two dozen organizations, at different stages of the project to further discuss specific aspects of the project and to collaborate on ongoing activities, including design of listening sessions and citywide parent survey as well as parent outreach.

While we did not systematically collect providers’ reflections on their challenges in providing ECE services, we discuss them in Part 1 of the report: Analyses of Enrollment & System Capacity Data and ECE Providers’ Perspectives. We elevated these and other providers’ concerns in our testimony earlier this winter and the most recent press release. Here are some of the examples of providers’ impact on some of the process-related decisions we made throughout the project:

- Providers suggested that we hold parents listening sessions virtually, rather than in person, as in their own programming, that was still what parents preferred and was the most accessible to them.

- Providers helped shape questions in the questionnaire we used for a citywide survey of parents by raising pressing issues of focus such as parents’ needs for extended day vs. school day care and the location of care.

- Providers informed what languages, other than English, would be the most useful in reaching parents they serve, such as Spanish, French, and Chinese.

- Providers shaped how we conducted outreach for the survey, including sharing the opportunity with parents through several social media channels that they already use to share information about their programming.

- Fewer providers suggested opportunities to connect with parents during in-person events. However, well planned in-person events were preferrable for providers who work with hard-to-reach populations, like immigrant households, non-English speakers, or families that don’t speak any of the languages we had the survey available for.

We held listening sessions with parents to understand:

- The barriers they face when attempting to access ECE programs.

- The solutions that would best support families in getting the care they need for their children.

- Who they see as responsible for implementing their parent-centered solutions.

We held 12 listening sessions with over 160 parents living in communities with large numbers of open seats in ECE programs based on our analysis of administrative data. Connecting with parents through partners in family-serving organizations helped broaden outreach to families with children not currently enrolled in any ECE programs and families with low incomes as well. We provided all partners with flyers for outreach and additional materials, available on our website.

Several themes emerged from these listening sessions, which can be read in Part II of our report: Parents’ Solutions for Early Care & Education Programs that Fit Their Families’ Needs. These themes formed the basis of our citywide survey of parents (see Appendix D in the report) regarding their ECE needs so that we could corroborate the barriers and solutions we heard from parents during the listening sessions with a greater share of NYC parents and caregivers.

We leveraged SMS text messaging for both the citywide survey of parents as well as establishing a way to maintain contact with parents and to share survey findings in four languages: English, Spanish, French, and Chinese. We chose these languages with the input of our family-serving partners as well as parents during the listening sessions. Using this SMS-based method ensured that busy parents and caregivers could start, stop, or pause the survey at will and take as much time as necessary to complete all the questions.

Strategies for Ensuring ECE Providers and Parents are Heard

Scaffolding opportunities to participate

While providers are trusted messengers, it is important to acknowledge that their capacity to support this research and advocacy on top of their already busy schedules is limited. This meant we had to provide multiple ways for providers to be engaged in ways that fit their availability. For example, providers could connect with us via email, or they could spend an hour attending our data sharing sessions to learn more about the findings we compiled throughout the project, both from qualitative and administrative data analysis, or participate in one-on-one meetings which we offered to all partners at multiple stages of the project. In addition to these options, providers also had the option to give feedback on our survey, and share the final report within their networks. More involved asks included reaching out to parents and sharing our flyers about upcoming listening sessions and parent survey or hosting outreach on site at a community center. We fully relied on providers to choose the mode of communication that best works for them and their families.

We also knew parents’ time was limited. For this reason, we created multiple ways to participate ranging from just a few minutes of time—such as taking the survey or reading about the results—to over an hour, by joining the listening sessions. Moving forward, we will continue to be mindful of the capacity of potential collaborators and we will ensure that there are opportunities for collaboration that would work even for those who cannot give much of their time but are passionate about the work.

Building trust

While a diverse range of zip codes were represented in both our survey and the listening sessions, we noticed more parents were listing zip codes in Manhattan than we were doing outreach. When consulting with partners on this issue—especially those who work with immigrant and families with low incomes—that there could be several reasons this, including a lack of trust in sharing the zip code where someone lives and instead reporting zip codes where they work. Even though zip codes protect anonymity, some parents may be concerned about how their information is used, and if it might be used against them. This speaks to the need to continue forging paths to connection with parents and caregivers as well as the need to continue these conversations with providers, who have invaluable expertise in not only providing care for families and children, but also in connecting with families and organizing them to attend events.

Reaching non-English Speakers

While we strived to reach providers and parents who are non-English speakers and less likely to get engaged, several providers also shared how they face the same challenges in their own work, especially in trying to reach families that might not be receiving services but could benefit from them. For example, we hosted listening sessions with family child care providers in English and Spanish, and developed materials for outreach to parents in three languages other than English.

Although we successfully reached and exceeded our target number of parents, our aim was to connect with parents who may be underserved by ECE programs, as they could be encountering significant barriers in discovering and participating in these programs. Advised by our family serving partners, we attempted to reduce language barriers by offering all our parent-facing materials in the four languages that were recommended by both parents and providers. It proved difficult to reach parents speaking non-English languages, and at times we found non-English speakers taking the English version of the survey. When sharing these difficulties with partners focused on similar outreach to parents, they faced the same challenges in reaching non-English speaking parents and caregivers.

Future Directions

The next phase of our participatory approach will be gathering feedback from parents and providers on their experiences participating in this project. This will help us ensure our findings and reports are useful not just for informing advocacy to improve child and family well-being but directly to the parents and providers themselves.

Over the next year, we will further engage providers as advocates and designers of strategies to better connect families with young children to ECE programs, and to further leverage these programs as opportunities to improve access to developmental and behavioral health supports both for children and for parents and caregivers.

Children’s healthy development and their family’s economic security are social goods—meaning all of society benefits when families with young children have access to essential supports. However, as our report indicates, thousands of families in New York City face barriers in accessing essential supports that help them thrive. That is why we continue this work and parents and providers’ voices will continue to shape our efforts.

Please subscribe to our E-Action Network to receive future reports and updates on the full range of our advocacy, research, and civic engagement programs. You can also read our Insight Post about this project’s data and how it informs solutions to the disconnect between parents and NYC’s ECE system as well as take action with us to advocate for data-informed ECE investments here.

Marija Drobnjak conducted the analysis of administrative data, supported outreach to ECE providers and co-authored The Youngest New Yorkers report. Cristina Onea coordinated outreach to ECE providers, led the coordination and facilitation of parent listening sessions, analyzed parent survey data, and co-authored this report. Bijan Kimiagar contributed feedback to an earlier version of this post.