NYC’s Digital Divide: 500K households have no internet access when it is more important than ever before

Digital Briefs

April 24, 2020

One of the most immediate and wide-ranging effects of COVID-19 has been the urgent need for internet access. As New York State continues into another month under stay-at-home orders, the digital realm has become a necessary space for everything from conducting everyday activities to meeting basic needs. Families experiencing economic and food insecurity must now navigate websites as programs like Food Stamps, Public Assistance, and Unemployment Insurance are processed online.

Additionally, great efforts are being made to bring health and behavioral health care services to those in need via tele-health or tele-psychiatry platforms, and public and private school systems have transitioned to remote learning. The digital realm is also essential to accessing critical health and safety updates and helps ensure family members, friends, and colleagues are able to sustain professional and social connections from a distance.

While remaining connected is critical on so many levels, internet access is not universal – more than 500,000 households in New York City lack internet access – and digital inequities are preventing the city’s most vulnerable populations from accessing financial and food supports, education, and needed health and behavioral health services in this time of crisis.

Mapping Digital Inequities In New York City

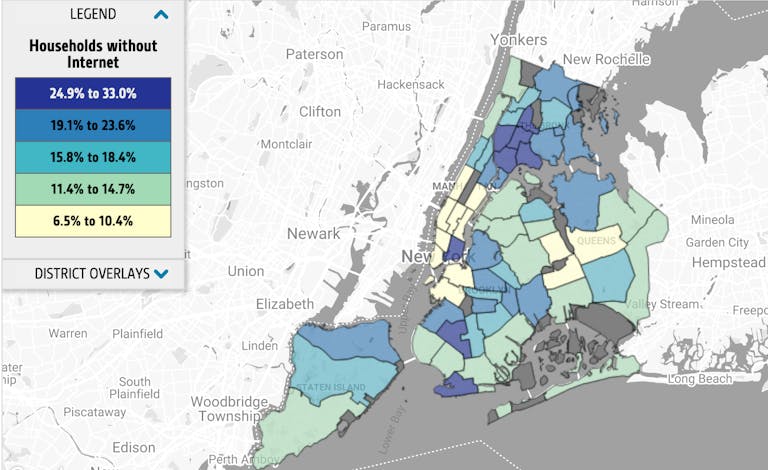

Just under one in six households across the city reported no means of accessing the internet in 2018 – that is, no dial-up, broadband, satellite, or cellular data plans.

SHARE OF HOUSEHOLDS WITHOUT INTERNET ACCESS BY COMMUNITY DISTRICT, 2018

Explore Our Data:

Households Without Internet Access >Households that lack any internet access are most prevalent in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty. 230,000, or 38%, of low-income households (earning below $20,000 annually) are without internet. In communities like Borough Park and Sunset Park in Brooklyn, and the Lower East Side in Manhattan, more than half of these low-income households’ lack internet access.

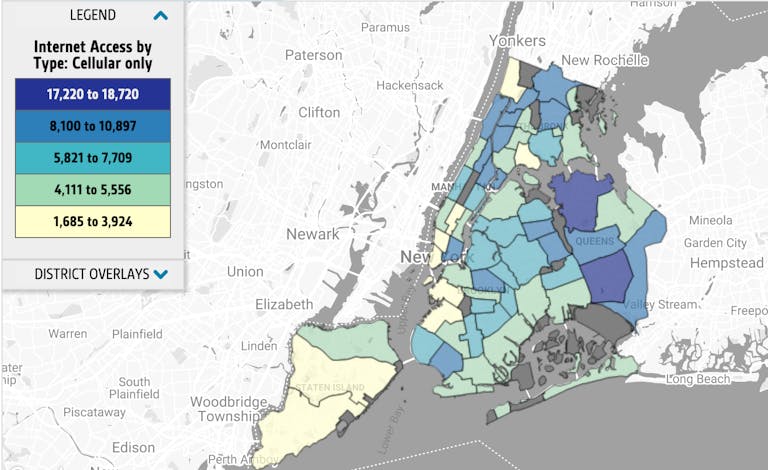

Further, the number of households that are accessing the internet exclusively through cellular data plans is growing: totaling 386,000, or 12% of all NYC households in 2018. This is up from 9% of all NYC households in 2015.

In a handful of community districts, more than one in five households access the internet through cellular data only – this is the case in Williamsbridge, Pelham Parkway, and University Heights in the Bronx, as well as Jamaica/St. Albans, Elmhurst/Corona, and Flushing in Queens.

HOUSEHOLDS WITH CELLULAR ONLY INTERNET ACCESS BY COMMUNITY DISTRICT, 2018

Explore Our Data:

Households with Cellular Only Internet Access >Finally, while the availability of broadband services is almost universal in New York City, not all households have access to choice among internet service providers (ISPs).

It is broadly accepted that three available ISPs is the minimum threshold to assure quality of service and prevent duopolies or monopolies in the market. Yet 14 percent of households citywide have only one ISP available within a block of their home.

In fact, as the map below shows, there are thousands of households in Northern Manhattan and University Heights and Co-op City in the Bronx for which there is only one ISP available.

Household Internet Service Provider Availability

(Click on a neighborhood to view the share of households with one internet service provider)

Households that lack any internet access are most prevalent in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty. 230,000, or 38%, of low-income households (earning below $20,000 annually) are without internet. In communities like Borough Park and Sunset Park in Brooklyn, and the Lower East Side in Manhattan, more than half of these low-income households’ lack internet access.

Further, the number of households that are accessing the internet exclusively through cellular data plans is growing: totaling 386,000, or 12% of all NYC households in 2018. This is up from 9% of all NYC households in 2015.

In a handful of community districts, more than one in five households access the internet through cellular data only – this is the case in Williamsbridge, Pelham Parkway, and University Heights in the Bronx, as well as Jamaica/St. Albans, Elmhurst/Corona, and Flushing in Queens.

Policy Considerations

Available data on the digital divide underscore the importance of expanding access to critical support services for New Yorkers facing risks to their well-being.

As the city, state, and federal government seek to address challenges related to COVID-19, it is especially important that we confront the digital divide to increase the flow of information to all households and ensure adequate participation in supports and programs that will be critical for recovery – including safety net programs, behavioral health and mental health services, and continued learning for students.

More than 800,000 New Yorkers live in households without internet, including thousands who participate in safety net programs:

Nearly 350,000 are SNAP recipients

More than150,000receive Cash Assistance

More than425,000are enrolled in Medicaid

15% of participants in these programs had no internet in 2018

Source: CCC analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample file (2018), 1-year estimates.

Recently, the NYC Department of Social Services released new information on HRA benefits. Among these changes, new HRA clients do not need to provide proof of their Medicare application for the period of the COVID-19 emergency, all active Medicaid cases will be extended, and no cases will be closed for failure to renew or failure to provide documentation due to potential digital barriers.

For those households whose internet access is limited to cellular data plans, HRA has improved enrollment measures through its ACCESS HRA online portal and app, and assistance is available by phone. However, the capacity of this digital infrastructure to handle the immense need at this time remains to be seen.

With the Independent Budget Office projecting close to half a million jobs lost in New York City, identifying ways to connect to and engage families in services will be vital moving forward. To that end, opportunities to bring free internet and data plans to New Yorkers who lack service should be explored, as well as capital investments to support bringing broadband to transitional and public housing especially where families with children concentrate. Households without internet connectivity lack access to key supports such as Unemployment Insurance, Public Assistance, SNAP, Medicaid, and WIC; the needs for these essential supports has been exacerbated by COVID-19. To mitigate such challenges, helping these households receive devices, data plans and internet connectivity is key, as is ramping up outreach and education efforts on available resources across multiple media – radio, mail, and phone – to raise awareness of available services and supports.

The COVID-19 crisis is fundamentally changing the way we approach teleservices and is likely to establish new modes of service delivery that will survive long after the height of this crisis. It is therefore essential that we ensure the systems that are established do not reinforce existing inequities for those who struggle to access services remotely. In particular, our health and social service systems must prioritize communities that do not speak English and ensure robust translation and interpretation services are provided so we do not further magnify language access gaps. Our systems must also adapt to communities and individuals who are less comfortable using teleservices and who are at risk of being left behind as this becomes a primary mode of service delivery.

Delivery Of Critical Behavioral Health Supports Must Be Sustained

Families and the nonprofit sector serving them must have necessary equipment or devices to carry out their work, as well as internet connectivity and access to personal mobile hotspots. In addition, creative solutions are necessary to support service delivery, benefit access and distance learning.

For instance, New York State has made important strides in providing flexibility for healthcare providers to offer new forms of telehealth and tele-therapy. This is critical in New York – where approximately 10.1% of all children in New York State ages 3-17 years have received treatment or counseling from a mental health professional during the past year, but among those children with a mental/behavioral condition, fewer than half (46.5%) received treatment or counseling.

OF NEW YORK STATE CHILDREN (AGES 3 TO 17) WITH A MENTAL/BEHAVIORAL CONDITION:

Received mental health

treatment or counseling

Did not receive

treatment or counseling

Source: 2017-2018 National Survey of Children’s Health.

As important as teletherapy is, it must not be viewed as the silver bullet for addressing children’s unmet behavioral health needs. Even with adequate resources, many families are struggling to adapt to services provided online. Some children may be too young to respond well to teletherapy, and many parents may struggle to engage in intensive dyadic therapy, particularly if they are facing the added challenge of providing educational support to the rest of their children. Lack of privacy with families sheltering in place is also an added barrier. Response and recovery efforts must address underlying shortages of providers available to serve children throughout the state. More fundamentally, we cannot effectively address the behavioral health of families without ensuring they receive the basic supports they need in the face of food insecurity, housing instability, and job loss.

In New York and across the country, COVID-19 is exacerbating children’s unmet mental health needs, as children face new behavioral health challenges resulting from isolation, economic and housing insecurity, disruptions in education, loss of loved ones, and heightened child welfare risks. It is critical that our City, State, and Federal governments focus not just on the immediate needs, but also the long-lasting repercussions of this crisis.

Funding must be dedicated to ensuring the children’s behavioral health service delivery system not only weathers this pandemic with providers given the training, equipment, and compensation necessary to continue serving the children in their care; but that system capacity is expanded upon to meet increased needs. Additional funding must also be devoted to behavioral health screenings, clinical care, and referrals capability during the summer months and upcoming school year cycle.

As important as teletherapy is, it must not be viewed as the silver bullet for addressing children’s unmet behavioral health needs. Even with adequate resources, many families are struggling to adapt to services provided online. Some children may be too young to respond well to teletherapy, and many parents may struggle to engage in intensive dyadic therapy, particularly if they are facing the added challenge of providing educational support to the rest of their children. Lack of privacy with families sheltering in place is also an added barrier. Response and recovery efforts must address underlying shortages of providers available to serve children throughout the state. More fundamentally, we cannot effectively address the behavioral health of families without ensuring they receive the basic supports they need in the face of food insecurity, housing instability, and job loss.

In New York and across the country, COVID-19 is exacerbating children’s unmet mental health needs, as children face new behavioral health challenges resulting from isolation, economic and housing insecurity, disruptions in education, loss of loved ones, and heightened child welfare risks. It is critical that our City, State, and Federal governments focus not just on the immediate needs, but also the long-lasting repercussions of this crisis.

Funding must be dedicated to ensuring the children’s behavioral health service delivery system not only weathers this pandemic with providers given the training, equipment, and compensation necessary to continue serving the children in their care; but that system capacity is expanded upon to meet increased needs. Additional funding must also be devoted to behavioral health screenings, clinical care, and referrals capability during the summer months and upcoming school year cycle.

Lack Of Internet Access Is Detrimental To Children Expected To Learn Remotely

Over 150K NYC children live in households without internet.

Including more than 100,000 school-aged children (5 to 17 years of age)

And nearly 80,000 school-aged children live in households with internet but may lack a device from which they can learn

Source: CCC analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample file (2018), 1-year estimates.

With schools closed for the rest of the school year, the city’s 1.1 million students have undergone the daunting challenge of transitioning to remote learning. While teachers and students have shown tremendous resilience during this time, many students, especially those in certain vulnerable populations, are struggling in the new environment.

The NYC Department of Education has been distributing laptops and iPads to students who need them, including students in shelter, but these students, and other temporarily housed students such as those in doubled up housing face multiple challenges, not just the digital divide. English Language Learners and students in immigrant families are also struggling with both the language proficiency and technological familiarity required to succeed in remote learning. And students with disabilities have had to receive their services virtually, and many have seen reductions in their individualized plans.

The City must continue to act quickly in getting devices with embedded data plans into the hands of students that lack them. In concert with this progress, the city must open Regional Enrichment Centers to students in temporary housing, and possibly other vulnerable populations, who lack the space, support and technology to effectively engage in distance learning. Moving forward, the city, state and federal government will need to undergo a thorough exploration into this period of remote learning. This starts with accurate and timely reporting on how many students are effectively engaging, and also includes assessing who was left behind, the extent of learning loss, and what structures and supports may be required over the summer and throughout the next school year as part of an educational recovery plan.