Health Equity for NYC Children Requires Environmental Advocacy

Insights

July 16, 2024

Summer in the city is when families pour out into parks and playgrounds to enjoy the sunshine and extra time with their children outside. Because of this, summertime is also an important reminder of the work needed to tackle environmental equity in our city. Summers are getting hotter, which has an impact on air quality and health outcomes, while also deepening the disparity in heat impact.

Environmental Justice & Air Quality

Before school was out for the summer NYC experienced a severe heat wave that once again brought up conversations about air quality and heat risk, especially with budget questions leaving New Yorkers wondering if libraries would be open as cooling centers come July 1. Thankfully, library funding was restored in the final budget which will help reopen some branches for thousands of residents on Sundays. But questions remain about how NYC can handle the heat when inequity persists, heat vulnerability and air quality issues such as park funding cuts remained, bus idling continues to pose a threat to community air quality, and the temps remain high.

This past week also came with a significant heat emergency warning about which even meteorologists expressed that “it’s unusual for the area to have such high humidity levels this early in the summer.” And when the heat rises, so does air pollution. Without the impact of intense sun and high temperatures, NYC air quality is regularly impacted by local and regional emissions and human activity. But even due to phenomena like weather patterns, as many New Yorkers learned definitively last year when New York was blanketed by orange skies and smoky haze resulting from Canadian wildfires, NYC is also highly susceptible to outside pollutants that double the impact of persistent issues.

Uncovering the Inequity in Air Quality Outcomes & Impact

NYC’s environmental justice areas (geographic areas that have experienced disproportionate negative impacts from environmental pollution due to historical and existing social inequities) are negatively affected at higher rates by poor air quality, among other environmental hazards. These communities are often low-income communities of color living near highways, power plants, and transportation depots that emit toxic pollutants (such as PM2.5, carbon monoxide, etc.) contributing to a decline in health and related conditions. You can view how different air pollutants impact different neighborhoods in this chart from the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. According to NYC data, almost all environmental justice areas have greater percentages of Black and/or Latine residents than NYC overall, and most are home to a majority of Black and Latine residents.

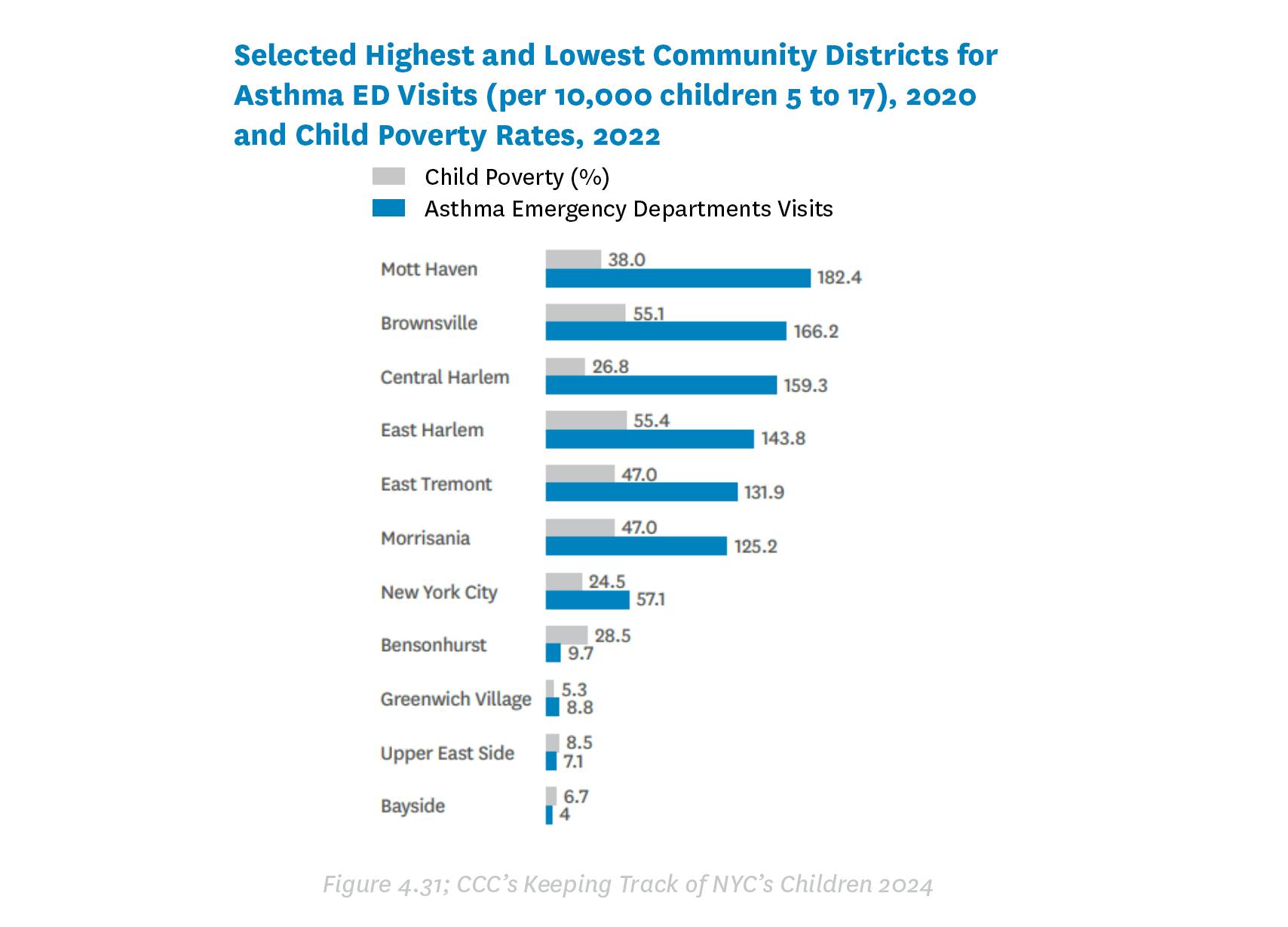

When we look at research around child well-being, we see an overlap between systemic racism, air quality, and child asthma. Analyzed in our latest 2024 Edition of Keeping Track of New York City’s Children, data shows that asthma is a leading cause of emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and missed school days in New York City (Fg. 4.28). Numbers also show that poverty is correlated with asthma prevalence (due to housing conditions and environmental racism). The highest rates of asthma emergency department visits for children are in neighborhoods that also have high rates of child poverty (Fg. 4.31).

(A select few communities such as Bensonhurst in Brooklyn, have less asthma ED visits despite poverty due to better environmental conditions like indoor air quality.)

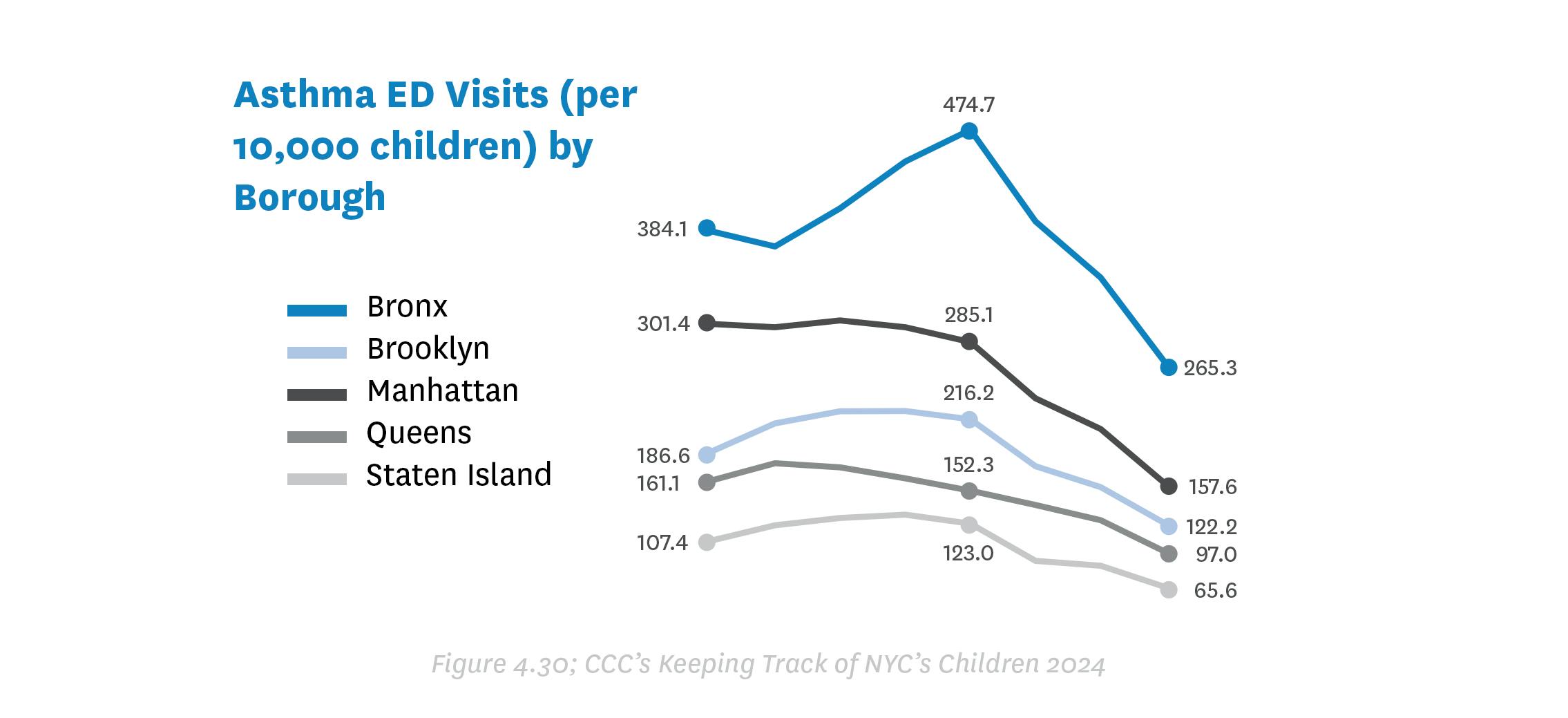

Historically, children who live in the Bronx have consistently experienced higher rates of asthma-related ED visits and hospitalizations compared to the rest of the city. Children under 5 have the highest asthma-related emergency room visits, which are almost three times higher for children in the Bronx than citywide (fg. 4.30).

The Bronx is home to some of the city’s largest, noisiest, and most polluted highways. Data also shows that children in the South Bronx were twice as likely to attend a school near a highway than children in other parts of the city.

Solutions & CCC’s Work

CCC has been a staunch advocate of environmental equity for children through coalition work, data, and policy. Last fall we stood by our partners to promote an important publication on the impact of bus idling on school children, Wake UP and Smell the Fumes: How School Bus Idling Harms Children and Communities. Idling of diesel and gasoline school bus engines poses a significant threat to the health and well-being of students, school bus employees and communities that house these school bus depots throughout the city. In response to this issue, Local Law 120 was passed in 2021, which mandates the transition to an all-electric school bus fleet in the city by 2035, and the transition is underway. It is important that we stay focused on preventing bus idling and pushing the transition forward as quickly as possible—many neighborhoods don’t have 10 years to wait for change. Some good news though: recently, Attorney General Letticia James announced a settlement agreement with four NYC bus companies in violation of the local law around bus idling that will require the companies to invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in electrifying their yellow bus fleets, as well as install anti-idling technology and train their workers not to idle engines. Read more on that here. This is a crucial agreement for NYC neighborhoods.

On a larger scale, CCC is part of a city and state coalition working to transition all state school buses to electric and is also a long-time supporter of the SIGH Act, which has now passed both the State Senate and Assembly Chambers and is at the Governor’s desk. The Schools Impacted by Gross Highways, or SIGH Act, is a bipartisan bill that aims to regulate how close new schools can be to major roadways, an issue mentioned earlier in connection with the Bronx that impacts child health. This would apply to controlled access highways, with newly constructed education facilities required to be at least 500 feet away, with some exceptions. We will be amplifying support for this bill in the coming weeks in an effort to get it signed by the Governor.

Keeping Environmental Justice in Focus

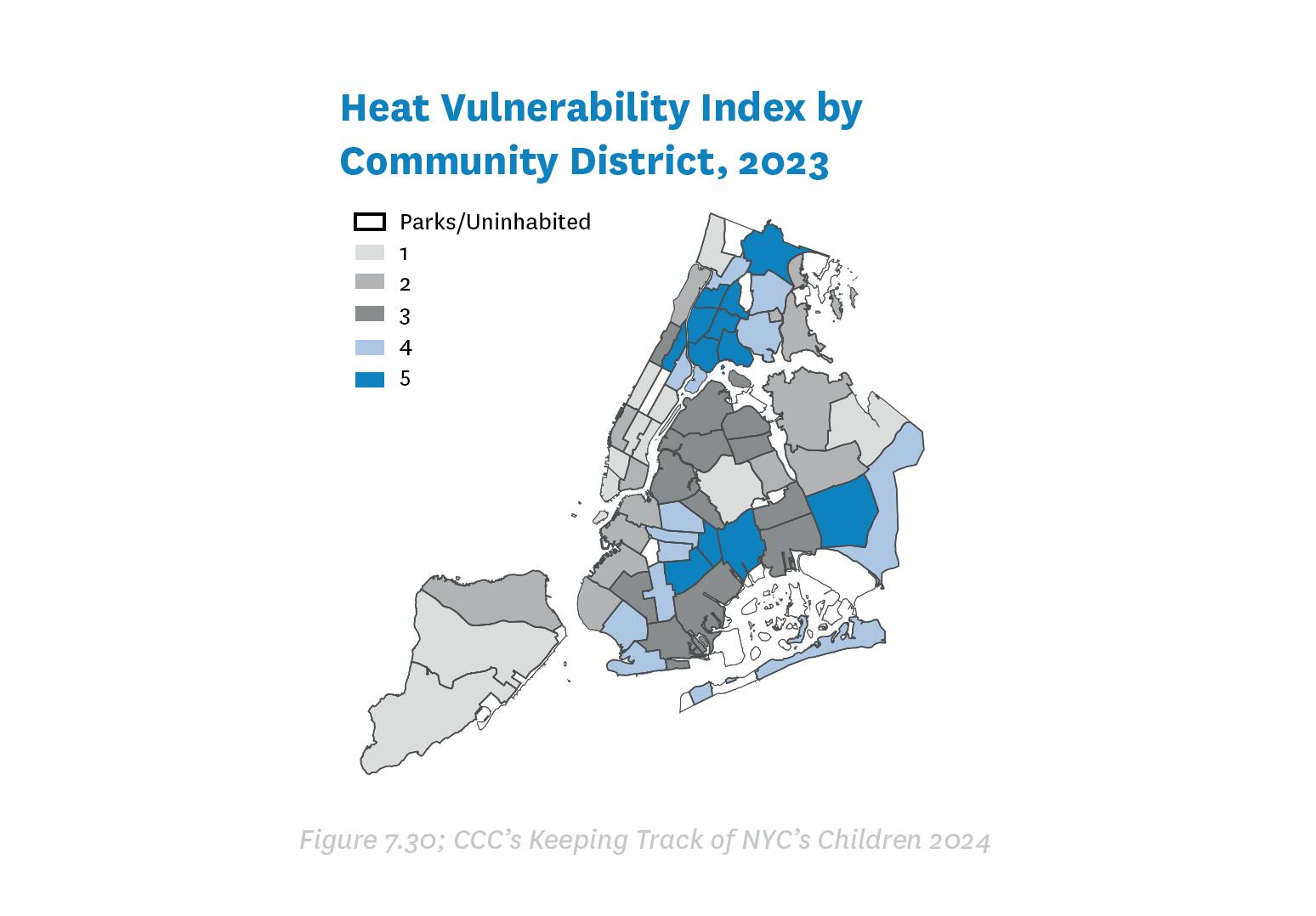

With already persistent air quality issues impacting children, the heat poses a uniquely higher threat to environmental justice communities. We know that last year NYC saw an increase in asthma related emergency room visits corresponding to the Canadian wildfires, and the majority of those visits came from zip codes in primarily Black and Latine communities, as well as zip codes with higher poverty rates, which you can read more about here. Black communities and neighborhoods are also disproportionately impacted by heat stress health issues, which you can see in the map below of community districts and heat vulnerability (Fg. 7.30). Communities in the Bronx, eastern Brooklyn, and south eastern Queens are the most impacted.

It is imperative that we continue advocacy work to improve air quality and mitigate heat impact for children’s health. When a child’s health is affected at such a young age (i.e. NYC children under 5 have the highest asthma-related emergency room visits) it can have lifelong consequences that perpetuate further inequity. To truly advance well-being, equity, and justice for all of New York’s children we cannot dismiss these significant environmental issues, especially as they overlap with education outcomes and poverty reduction efforts.